Sartre made much of the genius of Genet and his ability to reverse our perceptions of the criminal classes, the poor, and the queers who populated Genet’s life and his books. The saints and holy virgins of Genet’s universe are in fact the degraded criminals and homosexual degenerates of mid-twentieth century Europe. It was Genet’s purpose to reverse all this into a sacred paradox of filth and crime, one in which “(c)rime becomes the secret horror of grace; grace becomes the secret softness of crime” (from Sartre’s critical introduction to The Maids and Deathwatch, 12-13). The grace that Sartre ascribes to the men of Genet’s world has something to do with what Giorgio Agamben has described as “the ambivalence of the sacred” in which the sacred refers to precisely those things conventionally associated with the word, those pure and holy figures, places, and objects which remain within the light of God, and another form of the sacred which refers to “the person or the things that one cannot touch without dirtying oneself or without dirtying” (Agamben. Homo Sacer, 79). Sacred is the divine and the cursed. When we see the beggars and thieves assembled near the docks in Barcelona, filthy, wet, and abject as the French tourists put in for a stop-over and observe them as just one more picturesque sight amid the grand sights of Spain, we see this abject ambiguity in perfect splendor. Genet describes what transpires as the tourists go ashore:

Foreigners in this country, wearing fine gabardines, rich, they recognized their inherent right to find those archipelagoes of poverty picturesque, and this visit was perhaps the secret, though unavowed, purpose of their cruise. Without considering that they might be wounding the beggars, they carried on above their heads, in audible dialogue, the terms which were exact and rigorous, almost technical. (The Thief’s Journal, 164)

Of course they carried on without regard for the feelings or dignity of the beggars. These cast-offs were the sacred men, the accursed and damned who are beyond the reach of man and God, and are therefore not worthy of things like respect and dignity. So far removed from society and the civil realms of humanity, these men had no feelings, no sense of themselves as human, and there was simply no reason to consider them as such. Consequently, the beggars are observed as another picturesque feature of the landscape. They carry on, in Genet’s terms, like people of quality at a museum:

“There’s a perfect harmony between the tonalities of the sky and the slightly greenish shades of the rags.”

“… something out of Goya.”

“It’s very interesting to watch the group on the left. There are things of Gustave Doré in which the composition…”

“They’re happier than we are.”

(164)

So they observe and speak of all they see in the language of connoisseurs of fine art. The beggars and criminals, nothing more than inanimate objects placed before them to be interpreted and consumed. Yet, as objects devoid of speech, the beggars are elevated into sublime objects. They are more than what they actually are in their capacity as objects than as men. As human beings, they are degraded and foul, vile and defiled. As objects, they are picturesque in the sense of that old Romantic era category in which the object partakes of both the sublime and the beautiful, but in each case are of the order of things in nature rather than beings of social and cultural life. They are things which lack voice and have no real consistency in ordinary life. Invalidated socially due their criminal status, and economically due to their poverty, they are relegated to a space of being pure images of themselves.

Genet, of course, means to elevate his world of criminality, disorder, and filth so as to give dignity and grace to the very human individuals who have fallen to such horrible conditions and to impugn and condemn the world of society and power which takes its position as a natural inevitability but is in fact just as arbitrary and accidental as those who live in squalor. Genet made it his point to attack and condemn the violence and hypocrisy of power in his writing and in his life, and in his way, to depose and render inoperative the workings of domination and power. There is more, though, to the reversal of the paradox of the sacred in Genet’s fiction. The elevation of the abject that Sartre finds so captivating has at its core something far more profound which, just like Genet’s characters, functions at the margins of how power and the political function. Jacques Rancière’s notion of dissensus can provide an inroad toward understanding just what this marginal form of being can offer. In his “Ten Theses on Politics,” Rancière explains in Thesis 8 that the political is that space which preserves the presence of “two worlds in one;” it is a space which makes possible the preservation of two irresolvable modes of existence. Dissensus in the political sphere is differentiated from the sphere of the police whose only role is to clear the street, as it were, without taking account of what anyone has to say. In fact, they do not even recognize that anyone is a someone. As Rancière explains, the role of the police, as distinct from the role of the political, is “that which says that here, on this street, there’s nothing to see and so nothing to do but move along. It asserts that the space for circulating is nothing but the space for circulating” (Dissensus, 37). In declaring that this space is strictly for circulating and that we had better move along, it is implied that there is no interest in what anyone has to say because what anyone has to say has no bearing on what happens in this space. It is not a political space. It is a space for shutting the fuck up. The purpose of the police is to make sure those who do not have the status of a valid participant in politics remain silent. The inhuman grunts and clicks of the non-human are invalid, as is the gibberish of those who have been excluded from the political arena. The difference among humans would be those who have access to language which provides information toward the greater benefit of the common and those who simply articulate the common state of being. The former are politically valid, and the latter are invalidated beings of non-political space. A powerful political tactic would be to invalidate the language of political opponents so that you do not need to take into consideration anything they say. As Rancière tells us: “If there is someone you do not wish to recognize as a political being, you begin by not seeing him as the bearer of signs of politicity, by not understanding what he says, by not hearing what issues from his mouth as discourse” (38). We can invalidate a segment of the population by invalidating their language as viable political language, as the language of a degraded or criminal class that has nothing to offer the politically viable world of rational beings whose language is for the larger purposes of the common. The language of these degraded invalids may well be “groans or cries expressing suffering,” but this is not really language, and even if we allow that this suffering is real, it would be up to a valid speaker to speak up on their behalf. If no one speaks on their behalf, it logically follows that these alleged sufferings were not real sufferings, and were simply idle complaints. Those criminals suffering beneath the parapet in Barcelona were nothing more than animals who had fallen into some type of perdition by their own hands. Nothing to see here; move along.

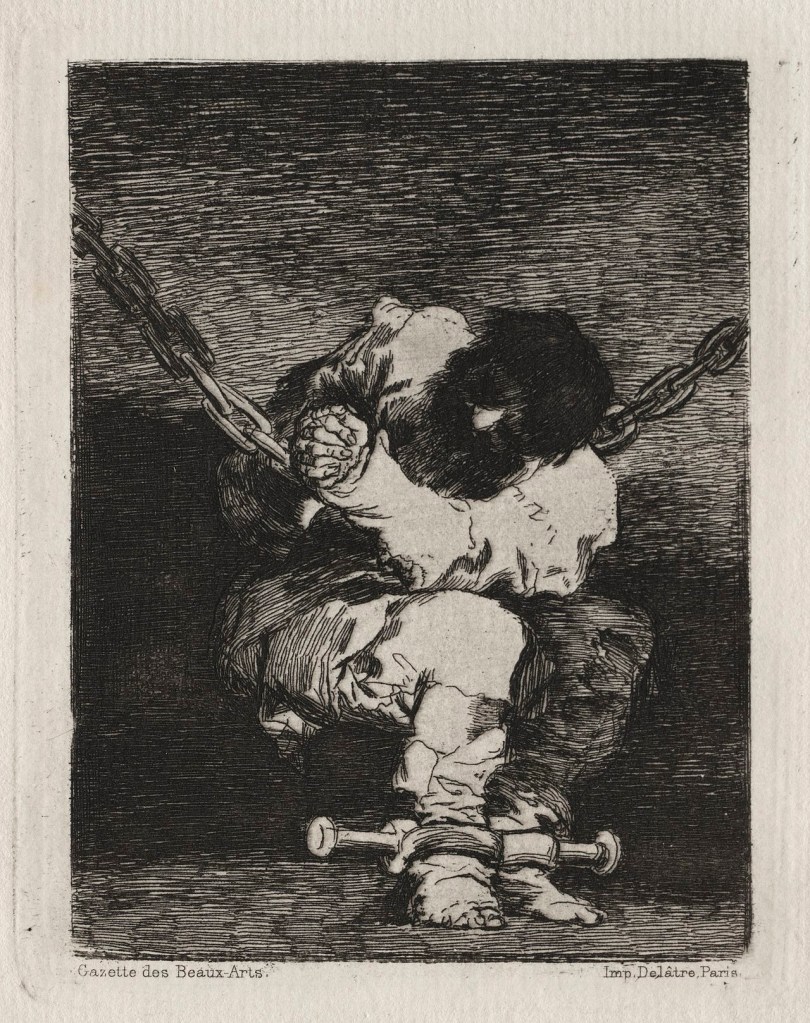

Tan bárbara la seguridad como el delito (“The custody is as barbarous as the crime”) Goya

Rancière’s thesis that dissensus is at the heart of what we call the space of the political means to place mutually exclusive forms of experience in a state of direct confrontation. Genet accomplishes his goal by placing the invalidated experiences of the criminal classes within the realm of experience and the spaces of the valid political language, of discourse. In this way, experiences of the invalid become the experience of the senses of everyone concerned, even if they do not like it. Dissensus forces two modes of life to unfold within the space of an aesthesis, or sensory realm attached to language: “The essence of politics is dissensus. Dissensus is not a confrontation between interests or opinions. It is the demonstration (manifestation) of a gap in the sensible itself. Political demonstration makes visible that which had no reason to be seen; it places one world in another” (38). For example, the placement of the abject beggars on the street against the polite world of wealthy privileged elites so that the objects these elites relegate to voiceless and senseless brutality emerge as not only living and valid humans, but humans who operate with a code of dignity and honor that is just as valid as that of the elites while the elites are seen as the callous, unfeeling, and inhuman brutes. Their language of gentile aesthetic appreciation transformed into that gibberish.

Genet’s worlds are the worlds of queer men during a time when they were considered degenerates and examples of the abnormal. What is more, these characters are criminals. They are filthy and they are perverts. Since these men have been adjudicated criminals they are designated as outside of acceptable social and political life. They have been legally invalidated as participants in the world. This population of people still exists. If anything, it has grown since we now have extra-legal modes of exclusion that bar people from full participation in social and political life. As I have written about elsewhere, credit checks and criminal background checks exclude people from access at all levels of life in our current society. Increasingly, background checking systems like CheckR are using AI to help further the scope of their criminal background checks, thereby adding a predictive capacity to these kinds of systems (Templeton. “Background Checks, Algorithms, the Re-making of the Abnormal.”). While it smacks of Philip K. Dick’s Minority Report, this is precisely what is going on in our society. The credit check also informs things like access to basic banking needs and housing, and where legal, is used in potential hiring decisions. Many employers view people with bad credit as potential liabilities in their workforce, and use credit checks as a way of screening for these liabilities. In all of these cases, people are invalidated in hiring decisions and in access to homes. In essence, these people are invalidated in life. Without meaningful employment, and lacking the ability to find a stable home, people are excluded from full participation in life itself. They may technically remain citizens of their communities, but they are lacking in every meaningful sense of citizenship since they are economically disempowered and may actually be homeless. Without an address, they might have no access to any kind of government assistance, a concept that is rapidly disappearing even as I write this. In short, these kinds of people become a class of invalidated people: the invalids. We used to use the term invalid to describe people we now commonly refer to as handicapped or differently abled. The term invalid remains appropriate to define those people who have been invalidated as thorough-going participants in economic life. Exclusion from economic life equals exclusion from social life. All of this inevitably translates to exclusion from political life since everyone who fits into the category of the invalidated is excluded.

Overladen on the invalid is the set of risks that come with them. Thieves have a tendency to steal, violent criminals have a propensity for violence, drug offenders have a tendency to use drugs, and they tend to steal and become violent. Those who demonstrate poor credit ratings have demonstrated that they are unable to meet their financial responsibilities and are therefore a risk for being irresponsible, if not outright thieves. There is an entire morality to the burden placed on the invalid. Maurizio Lazzarato has shown that debt itself carries a moral burden. Lazzarato references Nietzsche who showed us that “the concept of ‘Schuld’ (guilt), a concept central to morality, is derived from the very concrete notion of ‘Schulden’ (debts)” (The Making of Indebted Man, 30). Consequently, “debt results in the moralization of the unemployed, the ‘assisted,’ the users of public services, as well as entire populations” (30). Of the various demographics of “entire populations,” we may identify the invalid who are morally lax at best and downright immoral, if not amoral, at worst.

Lazzarato’s most important insights into the work of debt within social arrangements of the valid and the invalid lie in his observations of the biopolitical organization of contemporary life. Lazzorato explains that the rearrangement of the social and economic system under neo-liberal economics has led to a steady dismantling of the welfare state in favor of private insurance against personal disaster. This means the welfare state is no longer there for people when they hit hard financial times, but where they are lacking in cash, they can take on debt to make up any shortfalls. Entering into the debt relation is designed to empower people within the financial capitalist system since debt ideally enters one into the system by which income is generated from debt itself. This leads to a conception of subjectivity which Lazzarato terms “patrimonial individualism” (104). Our rights as citizens are re-interpreted as a right to debt but only under the condition that we are able to continue to meet our responsibilities as debtors. We do not pay back the debt entirely because paying? off debt interrupts the cycle of financial capital. Rather, we “pay” with our behavior. The biopolitical demands of financial capital, which is to day debt, are demands on our conduct in life in the form of our “conduct, attitudes, ways of behaving, plans, subjective commitments, the time devoted to finding a job, the time used for conforming oneself to the criteria dictated by the market and business, etc.” (104). In short, we become valid participants in social, economic, and political life insofar as we adhere to the demands of a world which values the morality and ethics of one who is in debt to others. To not meet your responsibilities is to become not just a bad business partner, but a bad person, a bad citizen, a bad subject—an invalid. Not properly human, even. Those who have been invalidated can be and will be excluded from active citizenship, and the more one becomes invalidated, the less one has access to the system that validates. To fall behind is to fall below. Being invalidated is of the same order as criminality.

There is a complete disenfranchisement that comes with invalidity.

There is a complete disenfranchisement that comes with invalidity. The stalwarts of the old days will insist that people still have the right to vote, that the people remain sovereign, and they are simply wrong. As Empire has colonized every atom of contemporary life, the rights of political citizens remain purely as formalities. What remains of electoral politics is pure show as the power of global capital outstrips the sovereignty of both the individual and the nation state. One last point from Lazzarato makes clear that the power of the debt economy within neoliberal economics and Empire functions “in such a way as to sweep aside the politics of ‘panels’ of citizens, experts and counter-experts, politicians, businesspeople, etc. It completely eliminates the consensual democracy” to which so many people still cling out of desperation (158). Under Empire, “(c)hoices and decisions concerning whole peoples have been made by an oligarchy, a plutocrisy, and an aristocracy” (159). While the valid remain full participants in what counts as the public sphere, the invalid are pushed to the margins and rendered silent, non-existent; their voices just the incoherent babble and that form of meaningless noise Rancière refers to when he describes language which does not rise to the level of discourse. Anyone should be able to see a potential danger in creating a population of people who have been made to shut up.

As financial capital swallows the entirety of social life, there emerge two absolutely opposed populations: the valid and the invalid. It is easy to simply write this off as the same as it ever was, that there has always been a criminal underclass that preyed on decent society. This would be fine except we are not talking about a small minority of antisocial “bad actors.” The invalid is a growing population of people who did not choose their status as invalid. According to the Consumer Financial Protections Bureau, 15 million people in the United States have medical debt on their credit reports. Jackie Wang explains that modern policing involves the use of algorithmic projections of criminality. This means police departments are using algorithmic data processing to project who might be engaged in criminal activity in order to act before a crime is being committed. At the time her book was released in 2018, 150 police departments around the country, including the New York City Police Department, had implemented programs like PredPol (Predictive Policing) and CompStat to track and potentially profile criminality before crime has been committed (Carceral Capitalism, 230). What this means is that anything that comes under scrutiny for algorithmic analysis is transformed into potential criminality simply by virtue of data selection techniques. Things like economically depressed parts of a city will be fed into the programs for increased scrutiny and attention. Anyone who happens to be poor enough to live in these areas will inevitably become a potential criminal, and a potential criminal is precisely what a criminal background check is designed to preclude.

Electronic digital analysis that produces hypothetical criminality can and is entered into other digital evaluative systems such as those used in background checks for employment. One’s status as a potential criminal cannot necessarily be prosecuted in the courts, but it can be used as evaluative data for employment. PredPol creates a geospatial box in populated areas for police officers to patrol as a space for high crime possibilities. This geospatial region is now the space of criminality. Wang explains that these areas become “a kind of temporary crime zone (241). If you happen to live in this temporary crime zone, you are now a data point of criminality. If you did not get a job because of a poor e-score, you may never know why because the data points that rendered you criminal are abstractions, mere ghosts of facts that have come to define who and what you are. You will simply be denied a job. Thus, the cycle of poverty continues. Debts cannot be paid. People become poorer, and they become more invalid as the ranks of the invalid grow. Invalidity does not depend on individual choice. The nature of capital as it is emerging in the Twenty-first Century is such that the digital systems of evaluation provide the data points by which one is rendered valid or invalid. The form-of-crime is the form-of-life. The substance of material life becomes what the form demands. To be in the class of the invalid is to have been dismissed from the political because we have been dismissed from the economic and the social. The invalids form an absence in all registers of modern society.

We have to wonder how long such conditions can persist as the ranks of the invalid grow and the valid dwindle. Already we see the wealthiest people in the world, those who ultimately determine who is and is not valid, advocating a separate world for themselves that would exclude any threat of the invalids. Slobodan Hayek described the plans of the wealthy in an interview with Democracy Now in which he sees “a vision of total decentralization… of turning the United States into a patchwork of fiefdoms or soft-corps… where people are opting in, paying to get into gated communities and then into a zero-sum social-Darwinist competition with the world beyond them.” The point is that the people who stroll the parapets looking down to admire the picturesque display of the voiceless poor and criminal class is upon us, not as an isolated image as in Genet, but as a principle of society. It is an extremely bad bet to imagine you are immune to becoming one of the invalids.

The question then becomes, as the invalid class grows, will we begin to see a growing reliance on criminality as a way of survival. The status of Luigi Mangione as a modern-day folk hero continues to grow. We are reminded of Clement Duval’s speech to the courts at his sentencing when he declared: “Ah well, this is the crime that I am here for: for not recognizing the right of these people to die of plenty while the producers, the creators of all social wealth, starve. Yes, I am the enemy of individual property and it has been a long time that I have said, along with Proudhon, that property is theft” (Duval. “Defense Speech.” Internet Library). Again, when the form-of-crime is the form-of-life, we are forced to reclaim the form-of-life as our own and in our own language. In the language of the form-of-life of the invalids, the valids are the ones excluded not by any known mode of constituted power, but by a power specific to destitution—destituent power. The constituted power of validity is such that it disempowers the very life of those who have been invalidated by rendering their language as invalid as political language. It is not the language of lives who have a meaningful way of speaking toward the public arena. As such, invalidity is made into what Agamben calls bare life; that is, life that is included in the juridical order, we are coded and controlled by capital in every way, but excluded from the order of social life, invalidated as through-going citizens and economic actors in the economic zone of contemporary life, which is the totality of contemporary life. Invalidity is the form of the exception as defined by Agamben in Homo Sacer. To claim the status of a form-of-life independent of the systems of validation would be to insist by a refusal to adhere to the standards of validation and to declare ourselves as “a life that can never be separated from its form, a life in which it is never possible to isolate something like a bare life. A life that cannot be separated from its form is a life which, in its way of living, what is at stake is living itself, and, in its living, what is at stake above all else is its mode of living” (Agamben. “What is Destituent Power.” 73). And this “way of living” begins in the first instance with a refusal.

Blanchot’s response to the attempts to ameliorate the crisis during the Algerian Civil War, the moment when those in power decided to preserve constituted power rather than justice, freedom, and even decency by allowing de Gaulle to take over as President, is a short piece that calls for a flat out refusal. The idea of refusal becomes increasingly important to Blanchot, but the simplicity of the idea at this stage in his political writing seems to capture where we are in our own present moment, a moment in which the very idea of the political appears almost quaint. Blanchot begins:

At a certain moment, when faced with public events, we know that we must refuse. Refusal is absolute, categorical. It does not discuss or voice its reasons. This is how it remains silent and solitary, even when it affirms itself, as it should, in broad daylight. Those who refuse and who are bound by the force of refusal know that they are not yet together. The time of common affirmation is precisely what has been taken away from them. What they are left with is the irreducible refusal, the friendship of this sure, unshakable, rigorous No that unites them and determines their solidarity. (Political Writings: 1953-1993. p. 7)

It is an irreducible refusal we require, and in many ways, the invalids have been living a life of irreducible refusal for quite a long time; it is the appearance of refusal in its non-appearance that has been lacking as the invalids now look to manifest this refusal “in broad daylight.” Blanchot’s idea of refusal is a blanket refusal, it is that non-engagement of the political that becomes political by establishing the meaning of an absence which is already present. Those who have been dismissed from meaningful participation in the economic and social spheres are effectively dismissed from the political spheres in the absence we comprise, and our overall refusal manifests this absence in the economic and social spheres. By refusing, one assumes a position of non-alignment with the general course of constituted forms of power by refusing to become part of the constituency which constitutes that power. Refusal gives body and meaning to those who have lost a voice. Blanchot explains further that “(w)hen we refuse, we refuse with a movement free from contempt and exaltation, one that is as far as possible anonymous, for the power of refusal is accomplished neither by us nor in our name, but from a very poor beginning that belongs first of all to those who cannot speak” (7). Refusal is not simply the stubborn position of saying “Nuts,” it is more far reaching, and this type of refusal is a strategic maneuver, one that we will need for the post-political world of today in which the Trump regime seeks to invalidate anyone who is not actively behind him in his consolidation of fascist power and oligarchical power.

Contrary to the almost childishly wishful thinking of the mass of political moderates and liberals in the United States, the Trump regime has no intention of engaging in political debates with their opposition, if for no other reason than they have no opposition, only enemies, and they mean to destroy their enemies. To engage this is a losing battle. Fascist power in its contemporary American form is a power constituted by the financial capitalism that drives it. The Musk Oligarchy takes the helm precisely because global financial capitalism is the real power. If it is currently expressed as American fascism through the clown man-baby king, that is a mere expedient. What is needed is a refusal, a general refusal that manifests the political absences as a presence. Refusal withdraws energy in the form of a destituent power; a power and a strategy which refuses the constituted mechanisms of fascist power by refusing to engage them. This is a strategy of withdrawal, of escape. Rather than attempting to hold up the silent voice of the voiceless up to the constituted power of the regime, a “destituent potential is concerned instead with escaping from it, with removing any hold on it which the apparatus might have” (The Invisible Committee. Now, 79). The crucial distinction between a destituent power or destituent potential is that previous forms of revolutionary and protest movements fail on two accounts: first, they are easily overwhelmed by the massive force of constituted power as it currently exists with its monopoly on state violence, and second, previous revolutionary strategies always reconstitute constituted institutional power in the precise image of everything it just opposed. In the case of a destituent potential, the strategy “is not primarily to attack the institution, but to attack the need we have of it” (80-81). The crucial insights of a destituent power is that it refuses the institutional form of constituted power by emptying that power from within, leaving only its form without its substance. The systems and their institutional bodies can spin their wheels with nothing on which to find a point of purchase: “The destituent gesture does not oppose the institution. It doesn’t even mount a frontal fight, it neutralizes it, empties it of its substance, then steps to the side and watches it expire” (81). This is what Agamben means when he explains that a destituent power renders constituted power as “inoperative,” it has no content on which the form may function (“What is a Destituent Power,” 72). Whereas the system which creates the distinctions which form the valid and the invalid demands engagement with specific digital mechanism of evaluation, a destituent refusal would begin by refusing the very institutions which operate with these systems and mechanisms in place, a destituent power begins by refusing all institutional forms built on the use of these evaluative mechanisms. Since so may of the invalid class are already excluded from full participation in these institutions, a unified refusal which manifests our absence is an ideal strategy which will render our absence as a dangerous and debilitating presence.

The invalid have become a new embodiment of Genet’s picturesque and voiceless cast-offs. Forming a growing population of those who have been disqualified as participants in contemporary economic life, these invalidated nobodies exist as the floral image of the untouchable classes who are there to reinforce the moral and ethical superiority of those who made the correct decisions in life and have found favor in the digital evaluative mechanism which placed them in their parapet of privilege. It would be incumbent upon the invalid to remove themselves from view, becoming imperceptible, and refuse to be present for the assembling of the people of quality. At that point, something uniquely powerful can begin to take hold. The invalid will begin to coalesce into an anonymous force of destitution, of absence, and refusal, and in doing so, become the palpable presence of the most menacing threat imaginable. Nothing there to smash or shoot, nothing to even see, but the most palpable absence. This is a destituent potential.

“The destituent gesture is thus desertion and attack, creation and wrecking, and all at once, in the same gesture” (The Invisible Committee. Now, 88).

Works Cited:

Agamben, Giorgio. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Tr. Daniel Heller-Roazen.

Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995.

–“What is a Destituent Power.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 2014,

vol. 32, 65-74.

Blanchot, Maurice. Political Writings: 1953-1993. Tr. Zakir Paul. New York: Fordham

University Press, 2010.

“CFPB Finds 15 Million Americans Have Medical Bills on Their Credit Reports.” April 29,

2024. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Accessed 3/28/2025.

Democracy Now. “Crack-Crack-Up Capitalism: How Billionaire Elon Musk’s Extremism Is

Shaping Trump Admin & Global Politics.” January 6, 2025.

Genet, Jean. The Thief’s Journal. Tr. Bernard Frechtman. New York: Grove Press, 1964.

The Invisible Committee. Now. Tr. Robert Hurley. Semiotext(e) Intervention Series No. 23.

Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017.

Lazzarato, Maurizio. Tr. Joshua David Jordan. Semiotext(e) Intervention Series No. 13.

Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011.

Rancière, Jacques. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. Edited and Translated by Steven

Corcoran. London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2010.

Wang, Jackie. Carceral Capitalism. Semiotext(e) Intervention Series No. 21.

Cambridge: MIT Press, 2018.

One response to “The Form of the Invalid and Destitutent Potential by Mike Templeton”

[…] to that work, we offer an essay by Mike Templeton titled, The Form of the Invalid and Destitutent Potential. Templeton provides us with a tour of how the destitute classes have been described, analysed and […]

LikeLike